On April 18, 2024 the UK Royal College of Physicians published E-cigarettes and Harm Reduction: An Evidence Review, the latest in a series of reports it has published since 2007 endorsing e-cigarettes for harm reduction. The report covers a wide range of topics, including assessing the health risks of e-cigarettes, the central question on whether or not they actually reduce harm. While the RCP no longer promotes the claim that e-cigarettes are 95% safer than cigarettes, the report is unequivocal in its conclusion about the relative dangers of e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes: “Using e-cigarettes for harm reduction to reduce morbidity and mortality from combustible tobacco is based on clear evidence that e-cigarettes cause less harm to health than combustible tobacco (page xvii)”.

As with the RCP’s conclusions about nicotine and e-cigarettes and stopping smoking, the conclusion is based on a small fraction of the available evidence, while ignoring the much larger body of relevant work showing that that e-cigarettes are associated with substantial disease risks in people, some indistinguishable from cigarettes.

As the report states, the conclusion that e-cigarettes reduce harms is based on evidence from two categories of biomarkers:

The first set are biomarkers of exposure, which are tobacco-related chemicals or their metabolites that can be detected in the human body; these include nicotine, tobacco-specific nitrosamines, volatile organic compounds, aromatic amines, polycyclic-aromatic hydrocarbons and metals. The second category are biomarkers of potential harm, sometimes referred to as biomarkers of effect, such as markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, which are signs of the effect of vaping or smoking in the body, for instance heart rate, blood pressure or lung function. Key diseases associated with these biomarkers include cancer and respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. These biomarkers are compared between people who vape, people who smoke, people who do both (dual use) and people who do neither (non-use). [page 68]

While there is nothing wrong with studying biomarkers, they provide only a limited window through which to assess risk of disease. They only capture a limited number of exposures and markers of adverse effects. The disease process is complex and a limited number of biomarkers may miss important effects. This is particularly important because e-cigarettes are not just cigarettes without some of the toxicants, but rather a different toxic challenge than cigarettes.

A complete assessment of the relative risks associated with e-cigarettes compared to cigarettes requires assessing actual diseases not just biomarkers.

The RCP never explains why they did not consider disease outcomes even though there was a large body of direct evidence available at the time the report was being prepared. In particular, of the 107 population studies that formed the basis for our meta-analysis Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes 92 were published as of February 28, 2023, when the RCP completed its search of the peer-reviewed literature on biomarkers.

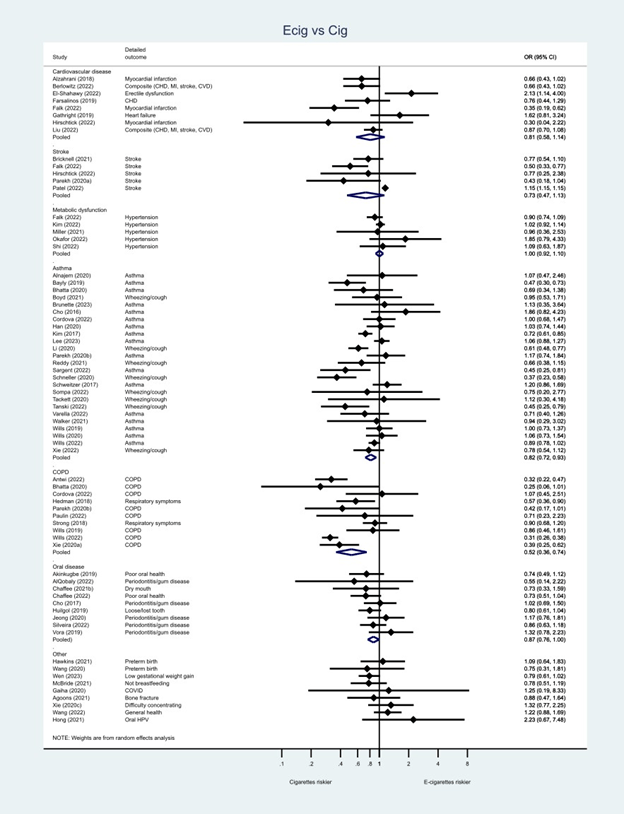

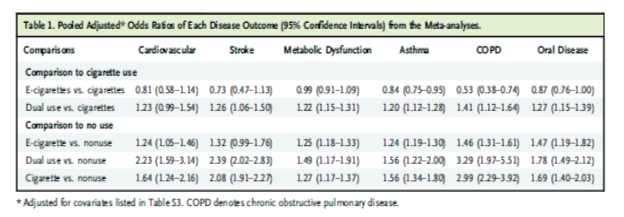

Meta-analyses of these 92 papers conducted using the same methods that the RCP used in its meta-analyses of biomarkers (figure and table below) shows that for cardiovascular disease, stroke and metabolic disorder e-cigarette risks are similar to cigarettes and for respiratory and oral disease, while lower risk than cigarettes, the risks are still substantial. Dual use (using e-cigarettes and cigarettes at the same time) is riskier than smoking alone for all outcomes.

Here are the specific results for the comparisons of e-cigarette risks to cigarette risks that the RCP ignored:

| Pooled adjusted* odds ratios of each disease outcome (95% CI) from the meta-analyses based on studies published by February 28, 2023. | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | Stroke | Metabolic dysfunction | Asthma | COPD | Oral disease | |

| Comparison to cigarette use | ||||||

| E-cigarettes vs cigarettes | 0.81 (0.58-1.14) | 0.73 (0.47-1.13) | 1.00 (0.92-1.10) | 0.82 (0.72-0.93) | 0.52 (0.36-0.74) | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) |

| Dual use vs. cigarettes | 1.27 (0.98-1.66) | 1.26 (1.06-1.50) | 1.24 (1.16-1.33) | 1.91 (1.11-1.28) | 1.46 (1.22-1.76) | 1.36 (1.12-1.64) |

| Comparison to no use | ||||||

| E-cigarette vs. non use | 1.31 (1.09-1.56) | 1.32 (0.99-1.76) | 1.26 (1.19-1.34) | 1.25 (1.19-1.31) | 1.52 (1.37-1.69) | 1.47 (1.19-1.82) |

| Dual use vs. non use | 2.23 (1.59-3.14) | 2.39 (2.02-2.83) | 1.60 (1.22-2.11) | 1.68 (1.28-2.21) | 3.29 (1.97-5.51) | 1.78 (1.49-2.12) |

| Cigarette vs. non use | 1.64 (1.24-2.16) | 2.08 (1.91-2.27) | 1.27 (1.17-1.37) | 1.61 (1.37-1.88) | 3.16 (2.39-4.18) | 1.69 (1.40-2.03) |

| * Adjusted for covariates listed in Table S3 of Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes. | ||||||

These are the same conclusions we reached in our meta-analyses of 107 papers available as of October 1, 2023, when we completed the search for our NEJM Evidence paper Population-Based Disease Odds for E-Cigarettes and Dual Use versus Cigarettes (one page plain English summary). For comparison, here are the meta-analysis results from all 107 studies included in our paper:

The bottom line: Risk estimates based solely on biomarkers underestimate the disease risk imposed by e-cigarettes. Some of these disease risks are indistinguishable from cigarettes.

Why did RCP ignore the direct epidemiological evidence?

Given this substantial and directly relevant evidence, one wonders why it was not even mentioned in the RCP report. Indeed, they did not even mention the existence of large-scale epidemiological evidence in the Limitations section of Chapter 5 of the RCP report to explain why they were not considering it.

5.3.8 Limitations of the reviewed evidence

The Nicotine vaping in England review by McNeill et al identified key methodological issues limiting the conclusions that could be made based on the reviewed evidence. To address some of these limitations, the updated review used stricter inclusion criteria for definition and duration of exclusive vaping and focused specifically on biomarkers of exposure that are directly associated with the development of cancer. Nevertheless, the new evidence was also restricted by the following limitations. First, there remains a lack of research exploring longer-term health risks of vaping. Only two new controlled trials—one RCT with 24-week follow-up and an NRCT with 12-week follow-up – were published since July 2021, and their findings mostly focused on relative (vs smoking) but not absolute (vs non-use) health risks of vaping. Secondly, most of the recently published longitudinal observational studies analysed data from the same source that were around 10 years old and hence did not adequately represent exposure to newer vaping products. Thirdly, sample sizes were often small. Finally, very few new studies explored vaping associations with changes in disease-specific biomarkers of potential harm or vaping effects on people with existing health conditions. Due to these recurring limitations, an international standard for assessing vaping health risks should be established and followed.

The report does call for “Large longitudinal cohort studies are needed: firstly, of people who vape and have never smoked, and secondly of former smokers who vape, and which adequately account for their smoking history (Page xvii).” The RCP ignores the fact that 24 of the risk estimates available as of February 28, 2023 were from longitudinal studies and 24 were assessing e-cigarette risks in never smokers. In any event, RCP’s call for specific types of epidemiological studies does not justify ignoring the large existing evidence base that these 92 (or 107) studies represent.

In addition, the RCP ignores the large pathophysiology literature that shows how e-cigarettes increase disease risk.

The RCP recognizes that England is an outlier in its approach to e-cigarettes

In the Introduction to the report, RCP recognized what an outlier England is on the e-cigarette issue:

Nevertheless, in endorsing and promoting vaping as part of a comprehensive national tobacco control programme the UK is an international outlier: few other countries have adopted this approach and none so consistently over the past 15 years. [page xiv]

The report goes so far as to say:

The RCP also understands that that the UK approach of embracing harm reduction as a complement to more conventional policy has been controversial and has attracted criticism, and does not seek to advocate that other countries should necessarily follow the UK in this approach. [Page 5, emphasis added]

Given the incomplete presentation of data – particularly omitting strong evidence that does not support its position – people outside (and inside) England would do well not to follow England’s approach.