Su Golder and colleagues paper “Vaping and harm in young people: umbrella review” sums up the large existing literature on e-cigarettes’ effects on youth, defined as people under 25. In contrast to systematic reviews which find and draw conclusions based on summing up individual studies, this umbrella review is finds and sums up all the systematic reviews on a given topic available as of November 2024.

In particular, the graph at the top of this blog post presents all the available systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the longitudinal associations between e-cigarette use at baseline among nonsmokers and subsequent smoking, measured in a variety of ways. The first group of 11 meta-analyses reported associations with any smoking; the second group of 4 meta-analyses reported associations with current or past 30 day (a common definition of “current”) smoking and so on. The numbers in parentheses give the number of individual studies upon which each risk estimate is based. Based on this analysis, Golder and colleagues concluded, “A consistent significant association between vaping and smoking initiation was found, supporting a causal relationship, with pooled ORs of 1.50-26.01 (21 systematic reviews), most of which suggested that young people using e-cigarettes are about three times more likely than those not using them to initiate smoking [emphasis added].”

In addition, Golder et al found “a substantial association between e-cigarettes and substance use, with pooled ORs [odds ratios] of 2.72-6.04 for marijuana, 4.50-6.67 for alcohol and 4.51-6.73 for binge drinking.”

They also found consistent evidence of adverse health effects:

- “Asthma was the most common respiratory outcome, with consistent associations (ORs: 1.20-1.36 for diagnosis and 1.44 for exacerbation).”

- “Three systematic reviews found associations between vaping and suicidal outcomes, and six included investigation of injuries, predominantly documenting explosion incidents.”

- “Significant associations between vaping and other harmful outcomes included pneumonia, bronchitis, lower total sperm counts, dizziness, headaches, migraines and oral health harms, but this evidence was largely derived from limited surveys or case series/reports.”

E-cig advocates’ continuing effort to discount the evidence

Another recently published paper, “Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review,” by Rachna Begh and other e-cigarette advocates (including many who have authored Cochrane analyses supporting e-cigs for cessation) assessed the evidence as of April 2023. Rather than providing an overall quantitative summary of the evidence, the paper systematically criticizes each study against often inappropriate (and in some cases practically unmeetable) criteria and concludes that they all have serious problems to the point that it is not worth doing a meta-analysis. Sam Egger and Martin McKee published a devastating letter to the editor detailing 17 ways in which Begh et al applied extreme,biased or inappropriate standards for judging quality of the studies. The authors’ response, which did not engage most of the specific criticisms, is here.

Nevertheless, given the strong consistency of longitudinal associations between e-cigarette use and subsequent smoking even they had to conclude, “At an individual level, people who vape appear to be more likely to go on to smoke than people who do not vape; however, it is unclear if these behaviours are causally linked. Very low certainty evidence suggests that youth vaping and smoking could be inversely related.”

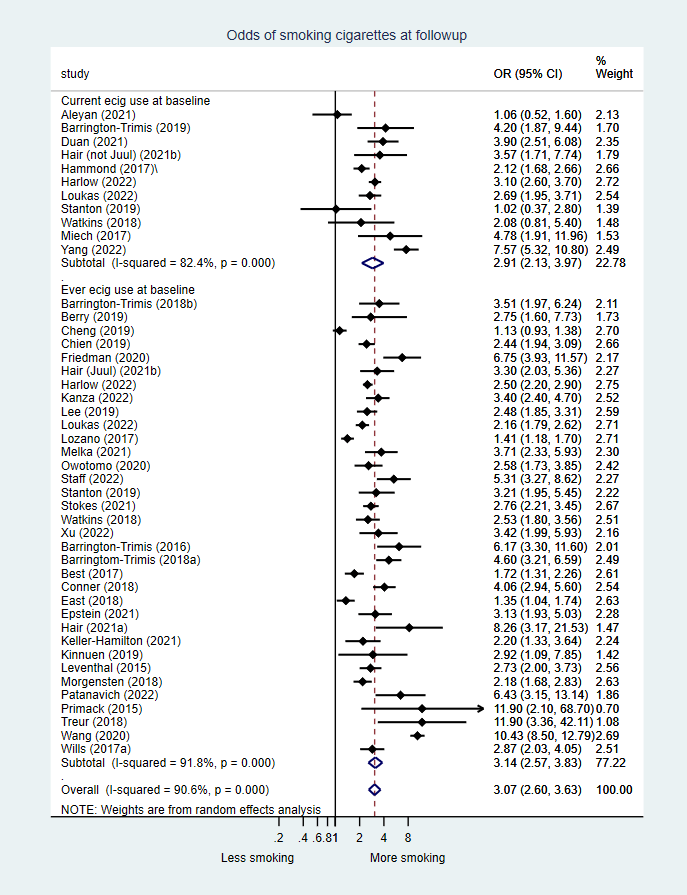

Based on the information they summarized, I did the random effects meta-analysis for them. What it shows is that there are a large number of longitudinal studies of the association between youth e-cigarette use at baseline and subsequent cigarette smoking, almost all of which show statistically significant increases in risk of subsequent smoking. The estimate of the odds ratio based on all the studies is 3.07, the same conclusion Goldr et al reached.

While, as Begh et al note, none of these studies is perfect, the fact that the results are so similar across a wide range of studies and over time strengthens the conclusion that the connection between e-cigarette use and subsequent smoking is real.

I hate to say it, but this strategy of trying to individually disqualify all the studies supporting an unpleasant conclusion or setting unmeetable standards is an longstanding tobacco industry strategy for ignoring inconvenient findings. So is obsessing about “causality”.

The time is long past for the e-cig advocates to start looking at the full forest of evidence and ask what we can reasonably conclude about e-cigarettes rather than concentrating on all the (different) blemishes on each tree.

Here is Golder et al’s abstract:

Objective: To appraise and synthesise the evidence on short and longer term harms of vaping in young people.

Data sources: KSR Evidence (systematic reviews); Medline, Embase, and PsycInfo (umbrella reviews); and reference screening.

Study selection: Systematic and umbrella reviews evaluating any potential harms from e-cigarettes in young people.

Data synthesis: Searches identified 56 reviews for inclusion from 384 unique articles. A consistent significant association between vaping and smoking initiation was found, supporting a causal relationship, with pooled ORs of 1.50-26.01 (21 systematic reviews), most of which suggested that young people using e-cigarettes are about three times more likely than those not using them to initiate smoking. Five systematic reviews demonstrated a substantial association between e-cigarettes and substance use, with pooled ORs of 2.72-6.04 for marijuana, 4.50-6.67 for alcohol and 4.51-6.73 for binge drinking. Asthma was the most common respiratory outcome, with consistent associations (ORs: 1.20-1.36 for diagnosis and 1.44 for exacerbation). Three systematic reviews found associations between vaping and suicidal outcomes, and six included investigation of injuries, predominantly documenting explosion incidents. Significant associations between vaping and other harmful outcomes included pneumonia, bronchitis, lower total sperm counts, dizziness, headaches, migraines and oral health harms, but this evidence was largely derived from limited surveys or case series/reports.

Conclusions: This study found that there were consistent associations between vaping and subsequent smoking, marijuana use, alcohol use, asthma, cough, injuries and mental health outcomes. The findings support the implementation of policy measures to restrict sales and marketing of e-cigarettes to young people.

The full citation is Golder S, Hartwell G, Barnett LM, Nash SG, Petticrew M, Glover RE. Vaping and harm in young people: umbrella review. Tob Control. 2025 Aug 19:tc-2024-059219. doi: 10.1136/tc-2024-059219. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40829950. It is available here.

Here is Begh et al’s abstract:

Aims: To assess the evidence for a relationship between the use of e-cigarettes and subsequent smoking in young people (≤29 years), and whether this differs by demographic characteristics.

Methods: Systematic review with association direction plots (searches to April 2023). Screening, data extraction and critical appraisal followed Cochrane methods. Our primary outcome was the association between e-cigarette use, availability or both, and change in population rate of smoking in young people. The secondary outcomes were initiation, progression and cessation of smoking at individual level. We assessed certainty using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE).

Results: We included 126 studies. For our primary outcome, there was very low certainty evidence (limited by risk of bias and inconsistency) suggesting that e-cigarette use and availability were inversely associated with smoking in young people (i.e. as e-cigarettes became more available and/or used more widely, youth smoking rates went down or, conversely, as e-cigarettes were restricted, youth smoking rates went up). All secondary outcomes were judged to be very low certainty due to very serious risk of bias. Data consistently showed direct associations between vaping at baseline and smoking initiation (28 studies) and smoking progression (5 studies). The four studies contributing data on smoking cessation had mixed results, precluding drawing any conclusion on the direction of association. There was limited information to determine whether relationships varied by sociodemographic characteristics.

Conclusion: At an individual level, people who vape appear to be more likely to go on to smoke than people who do not vape; however, it is unclear if these behaviours are causally linked. Very low certainty evidence suggests that youth vaping and smoking could be inversely related.

The full citation is Begh R, Conde M, Fanshawe TR, Kneale D, Shahab L, Zhu S, Pesko M, Livingstone-Banks J, Lindson N, Rigotti NA, Tudor K, Kale D, Jackson SE, Rees K, Hartmann-Boyce J. Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review. Addiction. 2025 Jun;120(6):1090-1111. doi: 10.1111/add.16773. Epub 2025 Jan 30. PMID: 39888213; PMCID: PMC12046492. It is available here.

The full citation for the Egger and McKee letter is Egger S, McKee M. Unreliable evidence from problematic risk of bias assessments: Comment on Begh et al., ‘Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review’. Addiction. 2025 Jul 5. doi: 10.1111/add.70143. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40616471. It is available here. There is no abstract.

The authors’ response is: Hartmann-Boyce J, Begh R, Conde M, Shahab L, Jackson SE, Pesko MF, Livingstone-Banks J, Kale D, Rigotti NA, Fanshawe T, Kneale D, Lindson N. Response to comment from Egger and McKee entitled ‘Unreliable evidence from problematic risk of bias assessments: Comment on Begh et al., ‘Electronic cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking in young people: A systematic review”‘. Addiction. 2025 Aug 12. doi: 10.1111/add.70166. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40798861. It is available here. There is no abstract.