Jessica Mongilio and colleagues just published an innovative approach to assessing the association between e-cigarette use and smoking, the so-called gateway effect, that provides insights between the link between e-cigs and smoking and how it relates to changes in youth smoking prevalence over time. In their new paper “Risk of adolescent cigarette use in three UK birth cohorts before and after e-cigarettes” the use data from three birth cohort studies in the UK that followed kids born in 1958, 1970, and 2000-2001 forward in time and assessed them every few years, including their tobacco use. In particular, Mongilio and colleagues assessed tobacco use when they were 16 or 17 years old in 1974, 1986, and 2018.

1974 and 1986 were well before e-cigarettes appeared on the market. They were well-established by 2018.

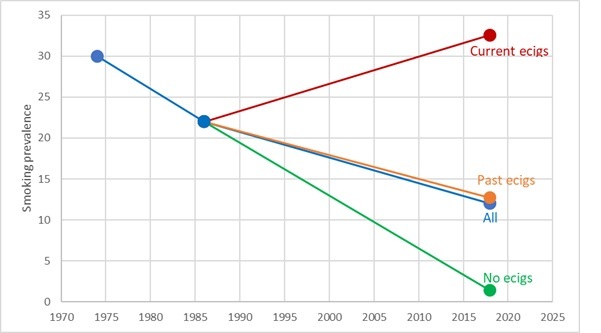

Consistent with all the other studies, they found that, overall, smoking rates (defined as smoking at least 1 cigarette a week) fell between 1974 to 2018, from 30% to 13% (blue line in the graph above).

The innovative thing they did was to separate youth in 2018 into three groups: (1) teens never used e-cigarettes, (2) teens who formerly used e-cigarettes (at least once a month), and (3) teens who currently used e-cigarettes (at least once a month). They then calculated the smoking prevalence in each group. They found:

- Very low prevalence of smoking (1.4%) among youth who never used e-cigarettes (green line in the graph), right on the trend established by the two data points collected before e-cigarettes became available

- Very high prevalence of smoking (32.6%) among youth who were currently using e-cigarettes, at rates comparable to those observed in the 1970s (red line on graph)

- Intermediate prevalence of smoking (12.7%) among former e-cigarette users (yellow line on graph)

In their analysis Mongilio and colleagues controlled for:

Child predictors:

- Ever drank alcohol

- Externalizing behavior

- School behavior

- Verbal ability

- Age

- Race (white vs non-white)

- Sex

Parental predictors:

- Father occupation (including unemployed)

- Mother education

- Mother smoking during pregnancy

- Parent(s) tobacco use

While the levels changed over time, they found that the effects of these variables was generally stable:

Many risk factors show similar magnitudes of associations with cigarette smoking across cohorts, conditional on the other included covariates. For instance, the odds of smoking were 2.87 times higher for NCDS youth [born in 1958] who had drunk alcohol (95% CI = [2.32, 3.56]), 4.37 times higher for BCS youth [born in 1970] who had drunk (95% CI = [3.00, 6.36]), and 3.15 times higher for MCS youth [born in 2000-2001] who had drunk (95% CI = [1.86, 5.35]), controlling for all other model predictors. In all three cohorts, greater externalizing behavior was associated with greater odds of smoking (OR ranging from 1.17 to 1.34), net of other risk and protective factors. In addition, school engagement and verbal ability scores were negatively associated with cigarette smoking at age 16/17 in all three cohorts.

This stability of the effects of these variables increases the confidence we can have that e-cigarette use was having an independent effect on smoking.

And, yes, the authors recognize that because e-cigarette use and smoking were measured at the same time, one cannot draw causal conclusions about the direction of the association just based on the statistics. (The other variables were assessed longitudinally, so support causal conclusions.) But the fact that the non-e-cig users fell on the historical trend but the e-cigarette users fell way above the historical trend certainly supports that the e-cigs were increasing the likelihood of smoking.

How much e-cigs increased smoking

Another strength of this study is that is provides a direct estimate of how much the presence of e-cigs in the UK market in 2018 increased smoking by 16-17 year olds. The paper estimates that the prevalence of smoking among youth who did not use e-cigarettes in 2018 was 1.7% and the overall prevalence among all 16-17 year olds regardless of e-cig use was 12%. Thus, the net effect of current or past e-cig use was associated with 7 times more smoking (12%/1.7%) than there would have been absent e-cigarettes.

This direct estimate is much simpler and more reliable that estimates based on trends from interrupted time series analysis, which can depend on the specific times used, number of data points, and statistical complications like autocorrelation among residuals, which few estimates account for.

A next step

Mongilio and colleagues have the data to answer another important question: Does e-cigarette use as a teen predict use in young adulthood? In addition to the data used in the present paper, MCS cohort [born in 2000-2001] members were observed at age 23, BCS members [born in 1970] at 26, and NCDS members [born in 1958] at ages 23. They could answer this important as yet unanswered question using an analysis similar to the one we used to show that US teen smoking longitudinally predicted young adult smoking in the US. Since they would be doing a longitudinal analysis using teen e-cig use and smoking to predict young adult behaviors, they could draw causal conclusions.

Here is the abstract:

Objective: Longitudinal data from three UK birth cohorts (born in 1958, 1970 and 2001) were used to (1) document the historic decline in adolescent cigarette smoking; (2) examine how e-cigarette use is associated with adolescent cigarette smoking in the most recent cohort; and (3) compare probabilities of cigarette smoking across the cohorts.

Methods: The prevalence of adolescent cigarette smoking was assessed in 1974 from 11 969 youth in the National Child Development Study (NCDS), in 1986 from 6222 youth in the British Cohort Study (BCS), and in 2018 from 9733 youth in the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS). Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds of adolescent smoking (ages 16-17) based on a common set of childhood risk and protective factors; adolescent e-cigarette use was included as a predictor in the more recent MCS.

Results: Adolescent cigarette smoking declined from 33% in 1974 to 25% in 1986 and to 12% in 2018. 11% of MCS youth reported current e-cigarette use. Though childhood risk factors for later adolescent smoking were mostly similar across the three cohorts, the risk of cigarette smoking in the MCS varied greatly by e-cigarette use. Among MCS youth, the average predicted probability of smoking ranged from 1% among e-cigarette naïve youth to 33% among youth currently using e-cigarettes.

Conclusions: Adolescents who use e-cigarettes have a similar smoking prevalence to earlier generations. Policy and prevention should seek to prevent adolescent nicotine exposure via both electronic and combustible cigarettes.

The full citation is: Mongilio JM, Staff J, Seto CH, Maggs JL, Evans-Polce RJ. Risk of adolescent cigarette use in three UK birth cohorts before and after e-cigarettes. Tob Control. 2025 Jul 29:tc-2024-059212. doi: 10.1136/tc-2024-059212. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40730479; PMCID: PMC12313170. It is available here.

Nice to see bunch of authors from my old Penn State!Sent from John’s iPhone

LikeLike